Manikins - Sensor technology for the well-tempered office

HVAC is starting to sweat

Thanks to sensor technology and mathematical modeling, smart dummies provide new insights into how workplaces can be brought to a comfortable temperature in an energy-efficient way and how to prevent patients from getting cold feet in the operating theater.

When the sun beats down on the facades in midsummer, the interiors of buildings with unshaded windows or poor insulation heat up mercilessly. If even the open window does not provide a cooling draught, it starts to get uncomfortable from a room temperature of 26 degrees. If the room temperature rises further, even less physically strenuous activities such as office work become a burden. Fans and air conditioning systems run hot. Switzerland is sweating.

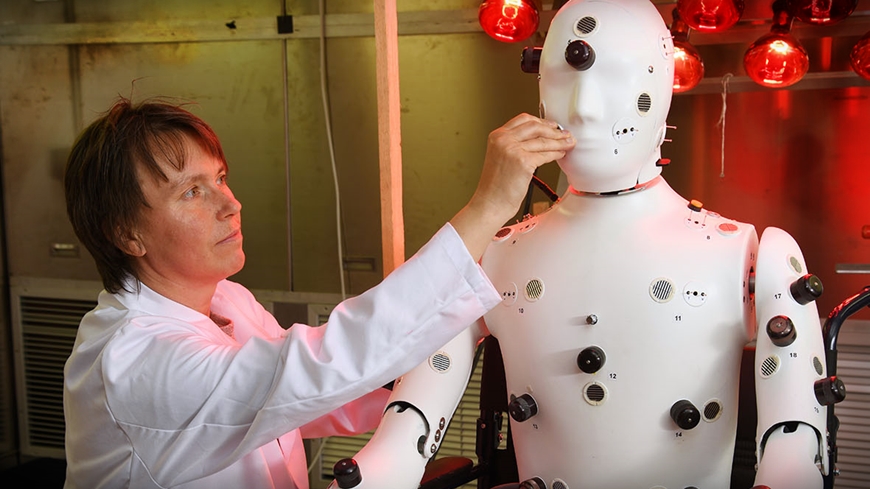

Energy consumption for air conditioning systems in Switzerland is now in the terawatt range every year, i.e. in the order of billions of kilowatt hours. It is uncertain whether the desired cooling in the room can be achieved at all. Empa researcher Agnes Psikuta has therefore set herself the task of generating reliable data on the indoor climate in the workplace. Her goal: to air-condition buildings much more sustainably – while at the same time maintaining people's health and performance. Her work colleagues: ANDI and HVAC, smart dummies that measure the indoor climate. Thanks to sensor technology and mathematical modeling, they recognize how workplaces can be sustainably brought to a comfortable temperature.

Sweating in the virtual office

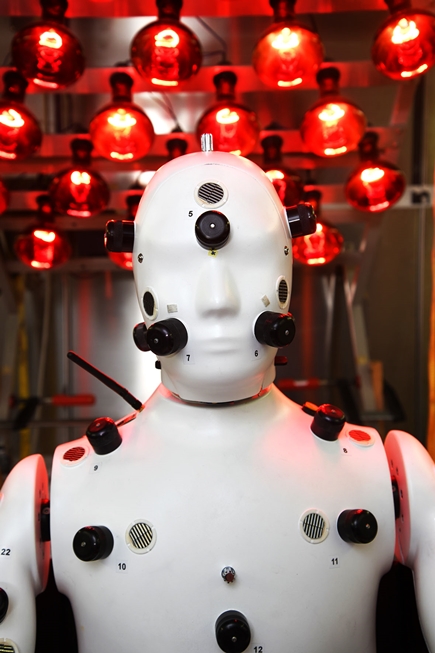

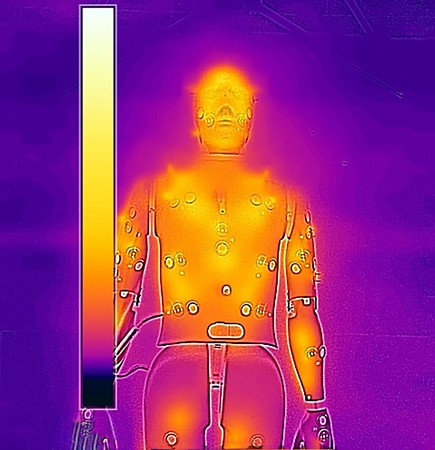

The futuristic-looking HVAC, short for Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning, is well equipped: However, sensors for air temperature, humidity and air movement alone are not enough. A total of 46 measuring fields break through the plastic shell of the manikin, which it uses to quantify the heat radiation from the environment and, for example, distinguish between heat from solar radiation and from the heating system.

Its partner with the simple name ANDI complements HVAC's data perfectly: "ANDI is the type for the big picture, it absorbs the heat balance that a person has under the given conditions," explains Agnes Psikuta from Empa's Biomimetic Membranes and Textiles laboratory in St. Gallen. To this end, ANDI keeps its operating temperature constant at 34 degrees, which corresponds to the skin temperature of a person in the comfort zone. Comfort zone here means that the body of a healthy adult can maintain a constant core temperature of 36.5-37.5 with minimal effort. "In the comfort zone, people don't sweat, they don't shiver from the cold and their hands and feet don't freeze because they can maintain their thermal balance with ease," says the researcher.

The mathematical modeling of this combined data ultimately results in a virtual thermal model of a person at work. In a project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), Agnes Psikuta is now working with partner institutes at the EPFL and the Polish Silesian University of Technology to investigate how HVAC and ANDI cope with the parameters of real office conditions over the course of the year.

Ultimately, it should be possible to optimize the energy requirements of buildings based on this work. "At the height of summer, air conditioning systems run at full speed to completely cool open-plan offices, for example. However, it is unclear how effective the situation is for the individual workplaces," says the Empa researcher. Structural elements directly at the workplace, such as cooling wall panels or ventilated office chairs, could provide more energy-saving and efficient solutions. The same could apply to the winter heating period: HVAC and ANDI could determine whether, for example, a room temperature of 17 degrees is sufficient if the workplace is heated locally to 22 degrees.

The ideal office

Legal requirements specify a range between 20.5 and 26.5 degrees for offices, depending on the outside temperature. (Guidance on Ordinance 3 to the Labor Act, State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SECO)

Dangerous hypothermia

However, the two manikins are also used in completely different situations – namely on the operating table. During a surgical procedure lasting several hours, it is important that the patient's body does not cool down too much, while the surgeon must not start sweating. If the patient loses too much heat, the risk of complications increases and the chances of a swift recovery worsen. "Previous options for keeping the patient warm enough, however, have consisted of unsustainable disposable solutions or cumbersome, difficult to disinfect set-ups," says Agnes Psikuta.

In a project with the Warsaw University of Technology, HVAC and ANDI are therefore investigating how easy-to-disinfect infrared lamps should be positioned in the operating room without obstructing the complex spatial conditions during the procedure. In addition, the heat radiation must not heat up the healthcare staff or even cause skin burns on the patient. While HVAC measures the heat flow from the lamp to the body with its dense matrix of sensors, ANDI calculates the entire heat balance of a patient, including the current room temperature. "The modeled data will be used to determine the position and output of the heat lamps for a wide variety of situations," says the Empa researcher. "In this way, we hope to be able to create ideal operating conditions without the risk of hypothermia."

Thanks to manikins: high-tech clothing and protection for firefighters

Dr. Agnes Psikuta

Biomimetic Membranes and Textiles

Phone +41 58 765 76 73

agnes.psikuta@empa.ch

Dr. Andrea Six

Communications

Phone +41 58 765 61 33

redaktion@empa.ch

The new NEST unit STEP2 (under construction) combines new digital design and fabrication technologies with innovative materials and a comprehensive energy and thermal comfort concept. The ultimate goal is to develop market-ready solutions that allow a sustainable use of energy and resources.

-

Share