Wound-healing sensors

Bandage with a voice

A novel bandage alerts the nursing staff as soon as a wound starts healing badly. Sensors incorporated into the base material glow with a different intensity if the wound’s pH level changes. This way even chronic wounds could be monitored at home.

All too often, changing bandages is extremely unpleasant, even for smaller, everyday injuries. It stings and pulls, and sometimes a scab will even start bleeding again. And so we prefer to wait until the bandage drops off by itself.

It’s a different story with chronic wounds, though: normally, the nursing staff has to change the dressing regularly – not just for reasons of hygiene, but also to examine the wound, take swabs and clean it. Not only does this irritate the skin unnecessarily; bacteria can also get in, the risk of infection soars. It would be much better to leave the bandage on for longer and have the nursing staff “read” the condition of the wound from outside.

The idea of being able to see through a wound dressing gave rise to the project Flusitex (Fluorescence sensing integrated into medical textiles), which is being funded by the Swiss initiative Nano-Tera. Researchers from Empa teamed up with ETH Zurich, Centre Suisse d’Electronique et de Microtechnique (CSEM) and University Hospital Zurich to develop a high-tech system that is supposed to supply the nursing staff with relevant data about the condition of a wound. As Luciano Boesel from Empa’s Laboratory for Biomimetic Membranes and Textiles, who is coordinating the project at Empa, explains: “The idea of a smart wound dressing with integrated sensors is to provide continuous information on the state of the healing process without the bandages having to be changed any more frequently than necessary.” This would mean a gentler treatment for patients, less work for the nursing staff and, therefore, lower costs: globally, around 17 billion $ were spent on treating wounds last year.

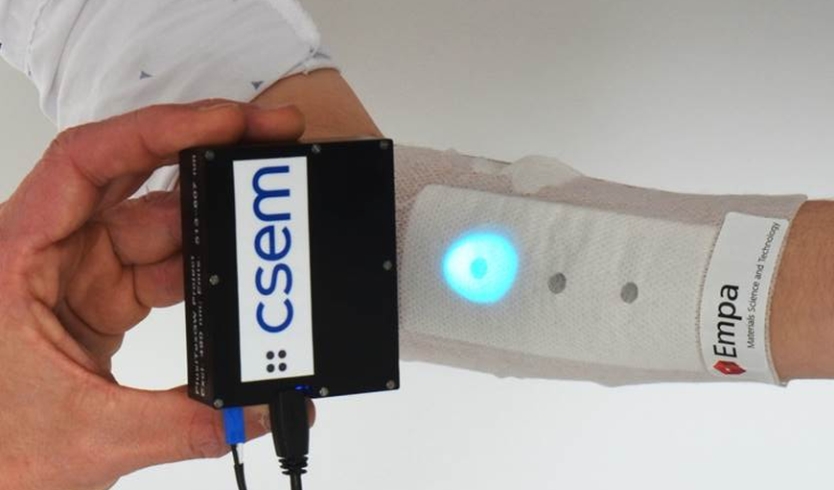

When wounds heal, the body produces specific substances in a complex sequence of biochemical processes, which leads to a significant variation in a number of metabolic parameters. For instance, the amount of glucose and oxygen rises and falls depending on the phase of the healing process; likewise does the pH level change. All these variations can be detected with specialized sensors. With this in mind, Empa teamed up with project partner CSEM to develop a portable, cheap and easy-to-use device for measuring fluorescence that is capable of monitoring several parameters at once. It should enable nursing staff to keep tabs on the pH as well as on glucose and oxygen levels while the wound heals. If these change, conclusions about other key biochemical processes involved in wound healing can be drawn.

A high pH signals chronic wounds

The pH level is particularly useful for chronic wounds. If the wound heals normally, the pH rises to 8 before falling to 5 or 6. If a wound fails to close and becomes chronic, however, the pH level fluctuates between 7 and 8. Therefore, it would be helpful if a signal on the bandage could inform the nursing staff that the wound pH is permanently high. If the bandage does not need changing for reasons of hygiene and pH levels are low, on the other hand, they could afford to wait.

But how do the sensors work? The idea: if certain substances appear in the wound fluid, “customized” fluorescent sensor molecules respond with a physical signal. They start glowing and some even change color in the visible or ultra-violet (UV) range. Thanks to a color scale, weaker and stronger changes in color can be detected and the quantity of the emitted substance be deduced.

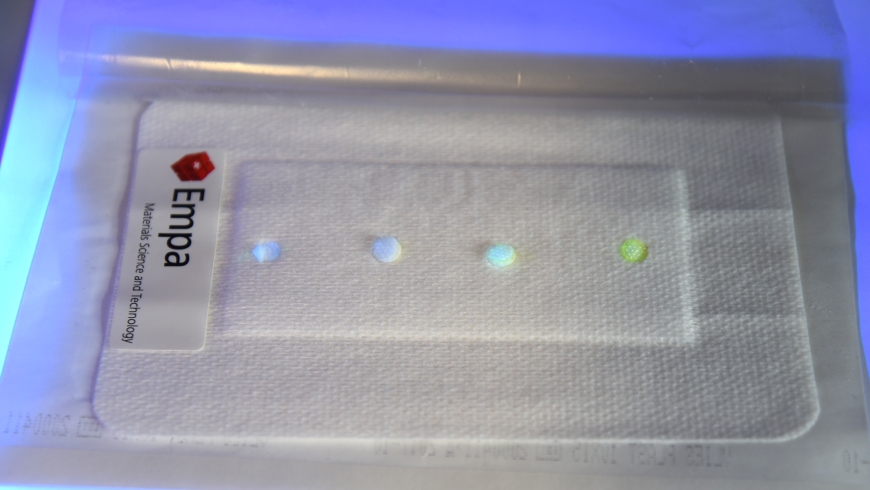

Empa chemist Guido Panzarasa from the Laboratory for Biomimetic Membranes and Textiles vividly demonstrates how a sample containing sensor molecules begins to fluoresce in the lab. He carefully drips a solution with a pH level of 7.5 into a dish. Under a UV light, the change is plain to see. He adds another solution and the luminescence fades. A glance at the little bottle confirms it: the pH level of the second solution is lower.

Luminous molecules under UV

The Empa team designed a molecule composed of benzalkonium chloride and pyranine. While benzalkonium chloride is a substance also used for conventional medical soap to combat bacteria, fungi and other microorganisms, pyranine is a dye found in highlighters that glows under UV light. “This biomarker works really well,” says Panzarasa; “especially at pH levels between 5.5 and 7.5. The colors can be visualized with simple UV lamps available in electronics stores.” The Empa team recently published their results in the journal “Sensors and Actuators”.

The designer molecule has another advantage: thanks to the benzalkonium chloride, it has an antimicrobial effect, as researchers from Empa’s Laboratory for Biointerfaces confirmed for the bacteria strain Staphylococcus aureus. Unwelcome bacteria might potentially also be combatted by selecting the right bandage material in future. As further investigations, such as on the chemical’s compatibility with cells and tissues, are currently lacking, however, the researchers do not yet know how their sensor works in a complex wound.

Keen interest from industry

In order to illustrate what a smart wound dressing might actually look like in future, Boesel places a prototype on the lab bench. “You don’t have to cover the entire surface of wound dressings with sensors,” he explains. “It’s enough for a few small areas to be impregnated with the pyranine benzalkonium molecules and integrated into the base material. This means the industrial wound dressings won’t be much pricier than they are now – only up to 20% more expensive.” Empa scientists are currently working on this in the follow-up project FlusiTex-Gateway in cooperation with industrial partners Flawa, Schöller, Kenzen and Theranoptics.

Panzarasa now drips various liquids with different pH levels onto all the little

cylinders on the wound pad prototype. Sure enough, the lighter and darker dots are also clearly discernible as soon as the UV lamp is switched on. They are even visible to the naked eye and glow in bright yellow if liquids with a high pH come into contact with the sensor. The scientists are convinced: since the pH level is so easy to read and provides precise information about the acidic or alkaline state of the sample, this kind of wound dressing is just the ticket as a diagnostic tool. Using the fluorescence meter developed by CSEM, more accurate, quantitative measure-ments of the pH level can be accomplished for medical purposes.

According to Boesel, it might one day even be possible to read the signals with the aid of a smartphone camera. Combined with a simple app, nursing staff and doctors would have a tool that enables them to easily and conveniently read the wound status “from outside”, even without a UV lamp. And patients would then also have the possibility of detecting the early onset of a chronic wound at home.

| Video |

Das intelligente Pflaster

-

Share