30th Empa Science Apéro

Seeking the secret of the Stradivarius

For centuries, the perfect tone of a Stradivari violin, such as the one played by Anne Sophie Mutters at the recent Lucerne festival, fascinated many music lovers. At the last Empa science forum in late August 2006, two scientists and a violin maker took the audience on the lookout for the secret of Antonio Stradivari.

|

Did the great violin maker use a special primer or varnish, did he treat the woods he used with minerals, or was it a fungus that gave the wood its special tone characteristics? Ever since, violin makers have tried to find the reason behind the differences in tones and paid careful attention to the quality of the wood used. But only ten years ago, scientists have become interested in the resonance properties of spruce fir, which is the most commonly used wood in violin and piano construction.

Christoph Buksnowitz of the Agricultural University in Vienna, explained to about 150 participants of the forum, that spruce wood is used in tone instruments since it contributes a lot to the development of sounds and because it was available in large quantities in close proximity to the early factories of musical instruments. Spruce fir used in violin making must have certain physical characteristics. Thus, for example, the diameter of the tree trunk must be at least 40 centimeters in order to allow for the size of boards needed in violin making. Tree rings must be spaced evenly about 5 millimeters apart in order to allow for perfect propagation of sound. Therefore, growth conditions play an important role, noted Busnowitz. Only wood from those spruce trees growing at their typical range and at heights of about 1,000 meters are therefore suitable. Too much light or wind from one side cause uneven growth and therefore the wood is of lower quality. In order to remove tensions in the wood, the trees must be dried naturally for some years. All these factors influence the formation and shaping of the most common cells of the spruce fir, the tracheids. When the cell walls of these tracheids become thin then wood density is reduced, and the wood becomes less heavy. Such a result is wished for in the making of violins because it allows for better resonance properties and sound radiation. However, this kind of wood is at the same time also less firm and this may negatively impact the stability of the violin. It appears then that the acoustic of a musical instrument is influenced by the cell structure of the wood. Experienced violin makers recognize the tone quality of the wood by its color. Thus, for example, the yearly formation of growth rings or a fungal decay of a tree will change the color. One may be tempted to ask therefore, why violins are still made out of so complicated a material as resonant wood and not out of a less variable material such as carbon fibers. Dr. Busnowitz thinks that «a lot of tradition is tied in with the resonance wood of the spruce tree, which is unique and individual in its form and tone features». |

||||

|

Fungi as useful helpers In the past, it was thought that a fungal decay of a tree brings about damaging effects altogether. Melanie Spycher in PhD work at Empa tried to show that this must not necessarily be the case to the tonal quality of the wood. |

||||

|

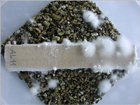

She infected sterilized spruce and maple wood pieces with different kinds of wood decaying fungi and allowed these fungi to grow for periods of from four to twenty weeks in a climatically controlled chamber. So far, the interim results of this probe are astounding, as Melanie Spycher puts it: «Different fungi work differently on various woods. |

|||

| With the split gill fungus, belonging to the group of the soft rot fungi, we could achieve suitable changes for violin making in the wood structure.» In June of this year, a patent was applied for. | ||||

|

The fungus reduced the cell wall thickness of the wood without impairing its firmness. Thus, the density of the wood was reduced thereby making the violin lighter and improving its tonal quality. Yet, the necessary firmness of the instrument was maintained. | |||

|

A soulless violin Michael

Rhonheimer’s profession of violin making could be soon

impacted through the ongoing research in the resonance of spruce

wood. Even today, Rhonheimer constructs resonant masterworks in his

Baden workshop, using nearly the same tools as were used in the

16th or 17th centuries, such as chisel, tuning hammer, saw, plane

and the botanic horsetail. Wood alone, however, does not determine

the quality of a violin’s sound. Other details, such as the

curvature of the upper and lower plates of the violin and the

positioning and size of the “F holes” play a role as

well. Until in this manner through costly handicraft a new violin

finally makes its sounds, one year goes by and the master violin

maker has spent at least 300 hours producing the instrument.

Editor: Contact: |

||||

|

|||